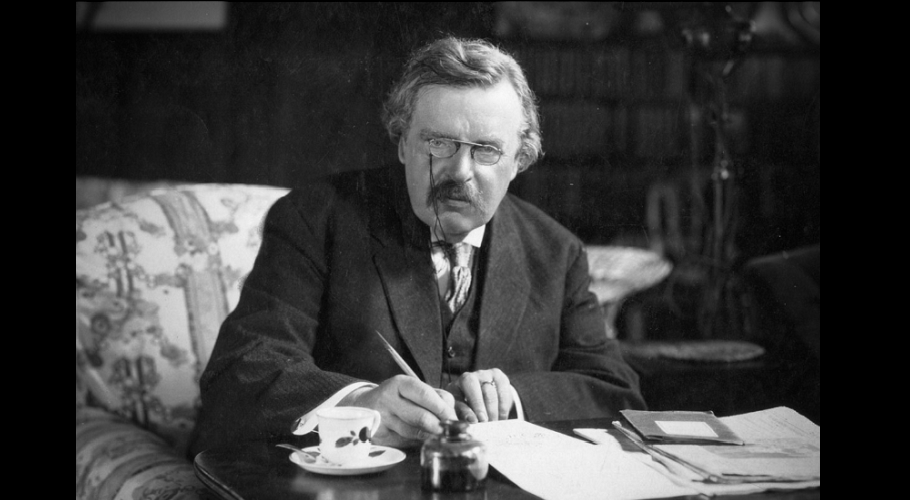

Gilbert Keith Chesterton was a prolific writer, and almost everything he wrote had an apologetic purpose, even the works he published long before his conversion to Catholicism. Of that vast production, which according to J. L. Borges “does not contain a single page that not offering happiness,” a handful of books stand out from the rest for the relevance of their themes, which overcame the journalistic urgency in which they originated, and the literary quality of their treatment. At the top of that category of excellence is usually placed The Everlasting Man, published in 1925.

Chesterton (1874-1936) thought of it as a response to the Outline of Universal History, an essay by his friend and intellectual rival, H.G. Wells, which had been published years earlier with overwhelming success (it sold some two million copies worldwide). It was an inspired reply. In it Chesterton displays the best of his pen: the ingenuity of his paradoxes, always effective; the wit, laced with humor, of his intellect; the ability to detect contradictions and weaknesses in modern ideas; and a rare wisdom born of vast readings that he had meditated on and assimilated over the years.

Using as an excuse Wells’ materialist historicism, which refused to register any hint of divine intervention, Chesterton set out to review how modernity has told the story of the world and the story of man. At the heart of his criticism was evolutionism and its theory of a gradual development of humanity from animal species, a notion that lost sight of the exceptionality of the human being. Evolution, he objected, does not explain human intelligence or its spirit.

The paintings found in ancient caves proved that man is differentiated from animals by species and not by evolution (“man knew how to paint reindeer, and reindeer did not know how to paint men,” he writes ironically). Hence any attempt to tell human history had to begin “with man as man; with man as something absolute and unique.”

This omission also extended to the no less exceptional fact of the birth of Jesus Christ and the Church. Despite the current academic argument, Christianity had not been a religion like the others of its time, nor had it been a reformed paganism nor had it appropriated, by adapting them, the superstitions current in the first century of our era. From the beginning it had been something very different, and the difference arose from the “singular human problem” posed by the life of Jesus. Chesterton said that, approached by an imaginary virgin reader of the New Testament, this complicated and contradictory life becomes incomprehensible if it is reduced to mere human criteria. The unique event of the Incarnation, he noted, “cannot be used as an element of comparative religion,” for the simple reason that there is nothing to compare it with.

Throughout the book Chesterton also draws up his own summary of universal history. Along the way, he points out bright spots (Babylon, Egypt, ancient China), crossed by sinister ones (such as those of Mexico and Peru, “refined to the point of worshipping the devil”). He makes observations that are very pertinent to our times. He suggests that if there ever was a matriarchy, it was only as a consequence of “moral anarchy”: mothers became the only permanent thing because fathers were anonymous and fleeting, and so patriarchy was, in reality, a progress and a benefit for women. He recalls that the culminating moment of civilization had the Mediterranean as its centre, a sea “into which the most disparate currents flow and unify.”

“In this circle of the orbis terrarum,” he writes, “is where the battle between good and evil is fought, the endless struggle of Europe and Asia, from the flight of the Persians at Salamis to the flight of the Turks at Lepanto; the duel in which the two perfect forms of paganism, Latin and Phoenician, faced each other, according to the flesh and according to the spirit.”

But this summit had limitations. The ancient pagan mythologies had not been a religion: they had calendars, but they did not have a creed. The pagans glimpsed the God who would satisfy their soul, but they did not go further (“speaking humanly…, the world owes God to the Jews,” Chesterton clarified). Christianity, on the other hand, quickly became the Church. Its appearance in history interrupted the decline of Rome, which “as with us, succumbed to the convergent action of the servile system and urban promiscuity,” and was sliding down the same nihilistic slope of Asia against which it had fought so hard. The birth in Bethlehem was, in truth, a new creation of the world, and it too began in a cave.

Chesterton warned of the risk of distorting the meaning of Christmas by overlooking the presence of the Enemy in Bethlehem, represented by Herod and his “devouring hatred for innocence.” Behind that “sweet, peaceful, simple thing” there was something very complex: “humility, joy, gratitude, mystical fear; but at the same time, alertness and drama.” The Church was born in that “great paradox of the cave.”

“It was important when it was still insignificant, when it was still powerless,” he stressed. “And it was important because it was intolerable, and it is fair to say that it was intolerable because, in turn, it was intolerant. It was hated because it had secretly and quietly declared war, because it had risen to destroy the heavens and the earth of paganism.”

There are other works by Chesterton that are more popular, that are more entertaining and more moving, but few had the influence of The Everlasting Man. Father Ronald Knox was “firmly of the opinion that posterity would judge it the best of his books,” an impression shared by Evelyn Waugh, another notable convert. C. S. Lewis confessed that, when he read it at a stage when he was struggling in the shadows of a vague theism, he was able to see “for the first time the whole Christian outline of history expressed in a way that seemed sensible to me,” and that was the first step towards entering into a personal relationship with God and reaching a deeper and more rooted conversion. Even J. L. Borges surrendered to its merits, despite the agnosticism that always prevented him from appreciating Chestertonian apologetics. In one of his last writings he praised that “strange universal history that dispenses with dates and in which there are almost no proper names and that expresses the tragic beauty of the destiny of man on earth.”

Jorge Martínez